For Black History Month, we’re delving into the Centre’s archives to learn more about Oxford Brookes University’s black heritage.

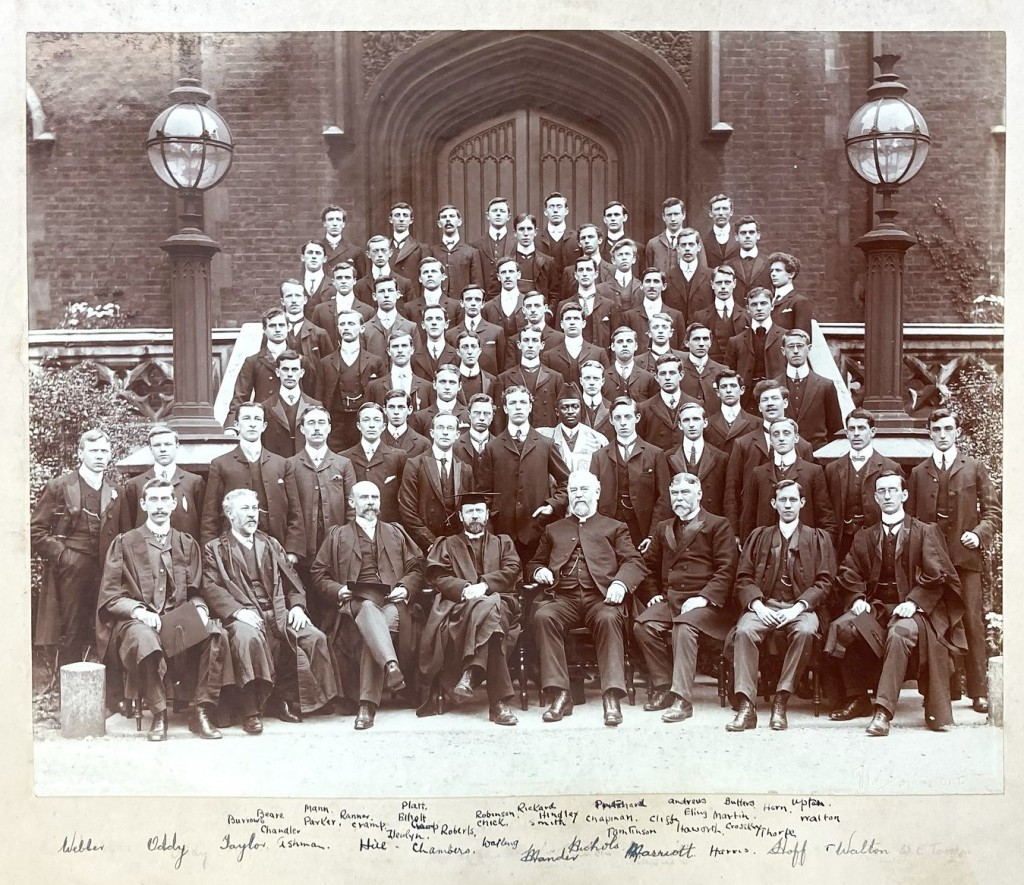

During a recent digitisation project, we made freely-accessible online a photograph album from the Westminster Training College archives dating from 1893 to 1912.1 This belongs to a series that commences in the 1850s and mainly features formal group shots of students, staff, and sports teams arranged chronologically. It is the most important visual record of the college’s earliest history.

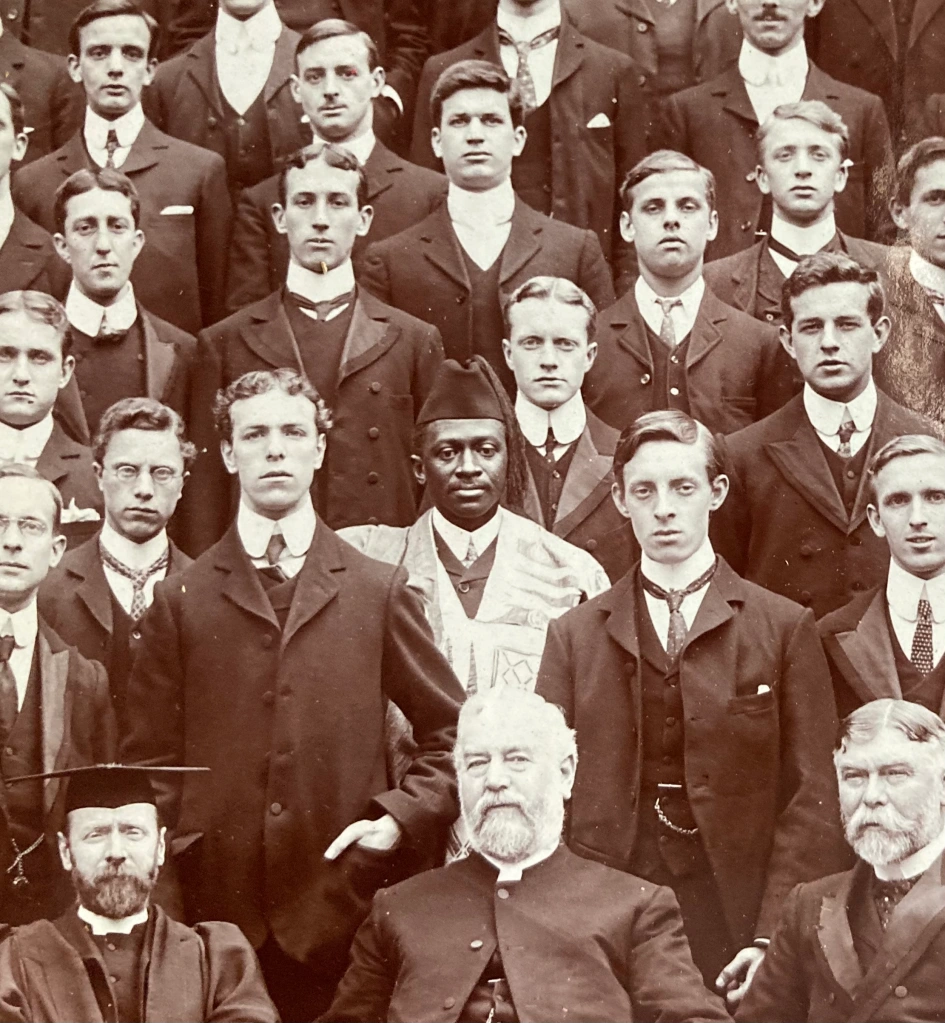

What’s remarkable about one Westminster College photograph for 1904-5 is that it is the first to include a black student. He stands prominently in the centre of the group, just behind the college staff and the chairman of the Union Society, and is proudly wearing a form of African dress over his suit. Notes alongside the photograph identify him as ‘Nichols’.2

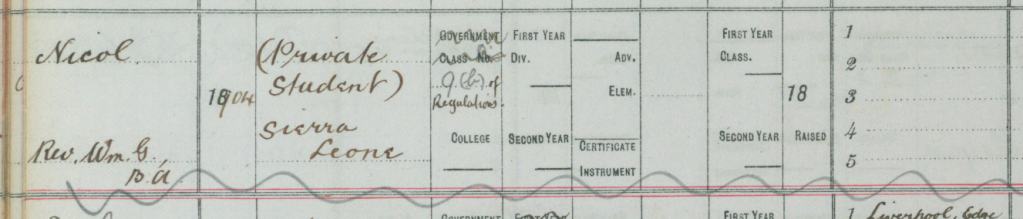

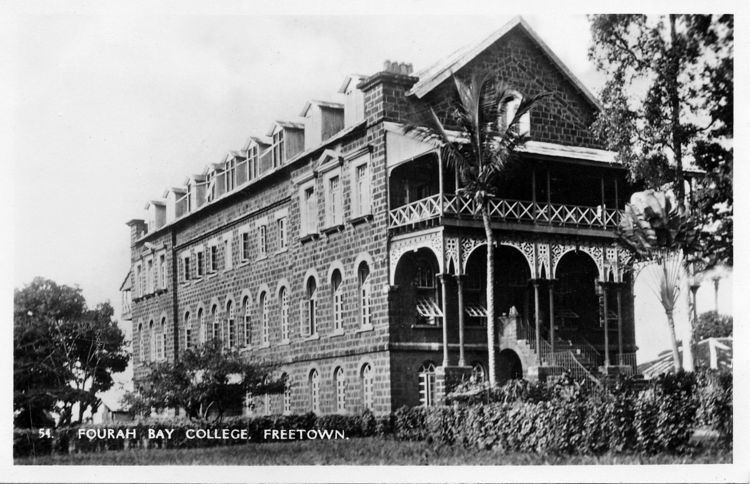

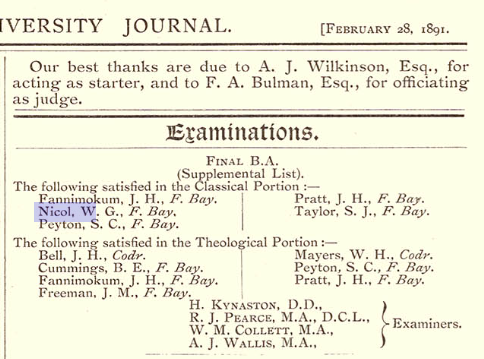

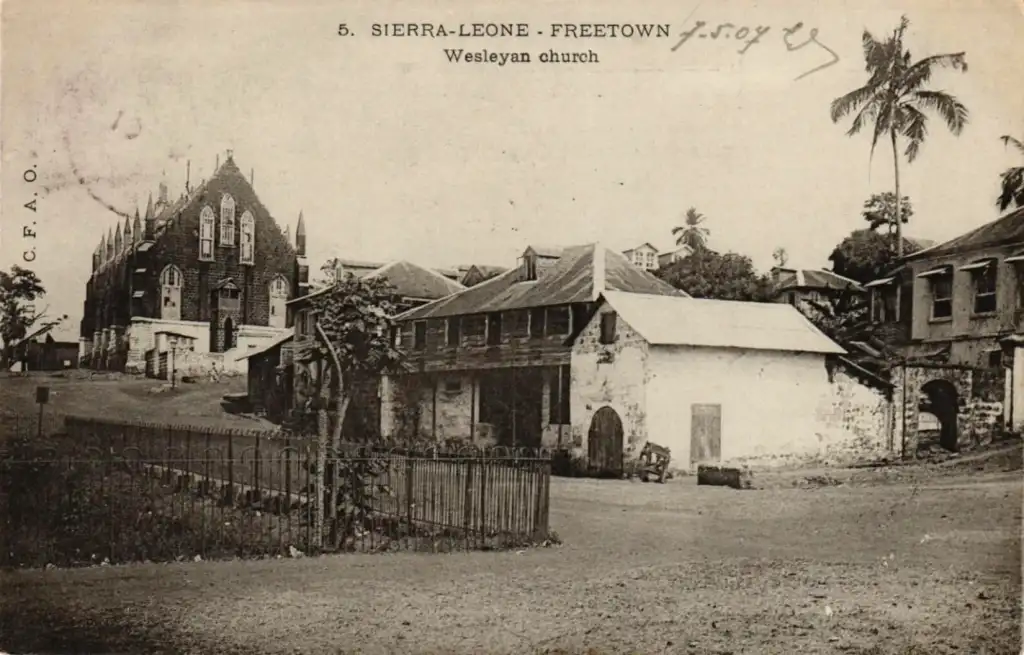

Corroboration with the Wesleyan Education Committee’s teachers’ register reveals this was the Rev. William G. Nicol of Sierra Leone.3 From a Creole background, Nicol was a graduate of Fourah Bay College in Freetown affiliated with the University of Durham; he matriculated in 1887 and earned his B.A. in 1891.4 Fourah Bay opened in 1827, and was dubbed the ‘Athens of West Africa’. It was the first Sub-Saharan establishment of higher education founded after the collapse of the ancient university of Timbuktu.5

Having earned his degree, Nicol was a tutor at the High School in Freetown. Already prominent in Wesleyan circles in Sierra Leone, in 1892 he was a public speaker during centenary celebrations marking 100 years of Methodism in the country.6 Nicol’s name first appears in the proceedings of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference in 1896, where he is described as a ‘native assistant minister’.7 The ‘assistant’ part was dropped in 1901 when he was ordained. ‘Native’ ministers were equipped for undertaking colonial duties, but were not permitted by the Conference to undertake positions in Britain.8

In 1903, Nicol was promoted to vice-principal of the High School, but he was destined for still greater things.9 £20 was raised by the Wesleyan circuit in Freetown to send Nicol to England to further his training at Westminster College and better qualify himself to succeed as principal.10 This step was supported by the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society and the Colonial Office.11

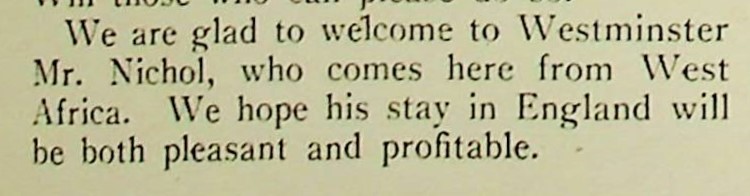

It was not uncommon in this period for Westminster students to go onto careers in the wider Empire. The registers record that they served in Australia, Canada, India, South Africa (and beyond) as teachers, inspectors, ministers, and missionaries.12 But Nicol was the first to come from Africa to England. His arrival was warmly acknowledged in The Westminsterian for May 1904, just as other students were concluding their classes for the year.13

Aged around 35-40, Nicol was senior to his Westminster classmates (and even some tutors) in age, academic, and ministerial terms – having been ordained and holding a Durham B.A. That said, it appears that he did engage with student life at the college. On 12 November 1904, Nicol addressed the Senior Debating Society on the subject of ‘Individuality’.14

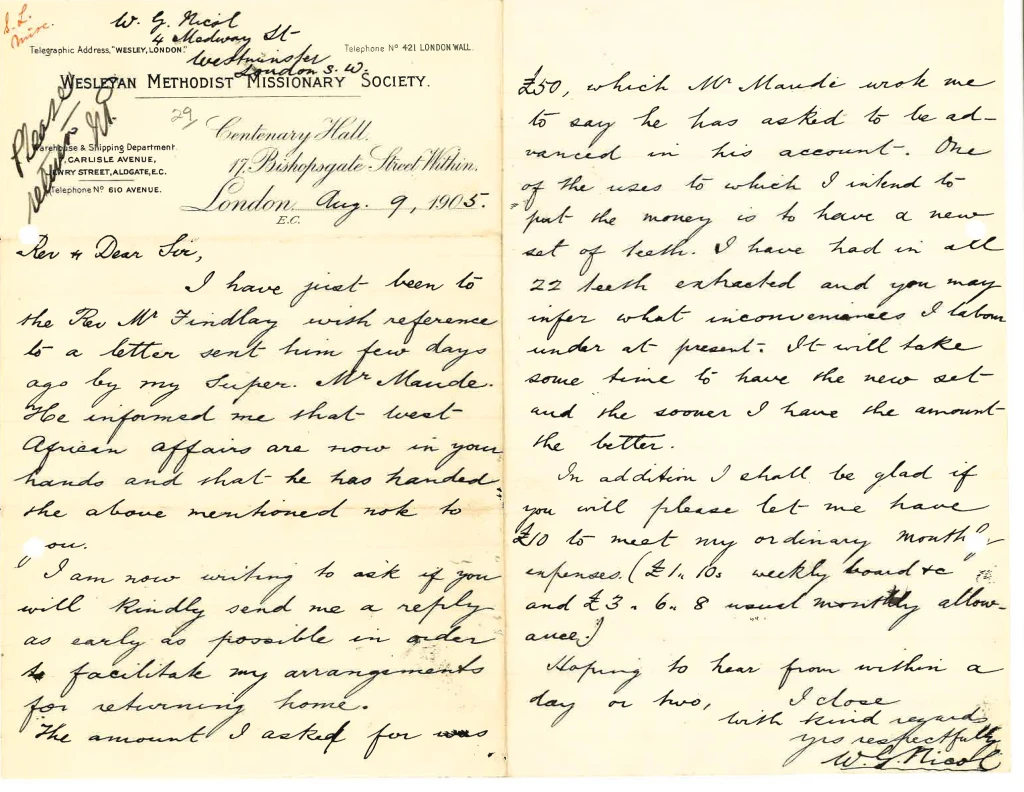

Surviving letters from Nicol’s time at Westminster mainly concern his accommodation and financial support. He lodged in Medway Street, immediately adjacent to the college site, and was reliant on regular maintenance from his teaching salary and the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society. Nicol also requested funds to buy a new set of teeth, having suffered twenty-two extractions(!).15

Nicol also participated in wider Wesleyan life in England, making appearances at local meetings and events. He can be identified as one of several preachers from Sierra Leone to address English congregations in the first years of the twentieth century.16 This sometimes brought cultural attitudes into sharper focus. In May 1904, shortly after his arrival from Sierra Leone, Nicol attended a Missionary Meeting in Guildford where he was described as ‘the centre of interest’. Newspaper coverage seemed as much concerned with describing his appearance in racialised language as providing an account of the speech he gave. Appealing to sensibilities of the time, Nicol addressed the meeting about the progress of missionary work and said,

He stood there that night of living proof of Methodist evangelism and self-sacrifice, by which thousands of his brothers in West Africa had been emancipated from heathenism

In Methodist circles, as elsewhere, attitudes towards people from Africa were still openly caricatured and racially-stereotyped. The June 1904 issue of The Westminsterian referred glowingly to a performance at the college by a blackface minstrel troupe, then still a common form of popular entertainment.17

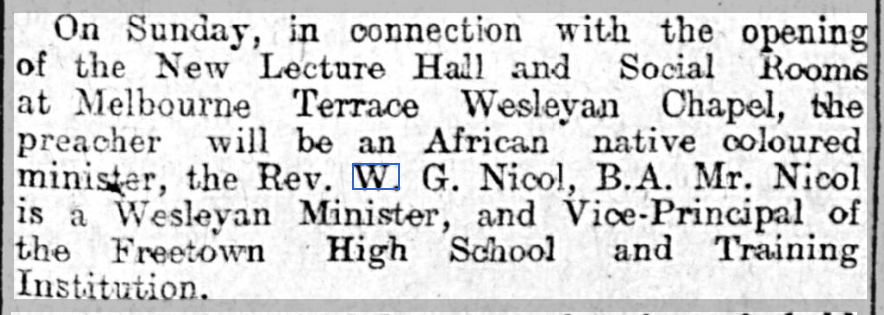

But other appearances by Nicol were reported in less contentious terms. In August 1905 he was a guest preacher at the opening of the new Lecture Hall and Social Rooms at Melbourne Terrace Wesleyan Chapel in York.18 This may have been on his way to or from Durham, where he received a Masters degree for the ‘excellence’ of a paper on Socialism.19

Nicol returned to Sierra Leone at the end of his year at Westminster College, and successfully took up the principalship of the High School and Training Institution in Freetown. He is recorded in that post in the Wesleyan Methodist Conference minutes until 1911 when he left the Connexion.20

Subsequently, Nicol undertook ministerial and teaching work in the Niger Delta.21 By 1914, he was leader of a ‘foreigners church’ in Calabar, in modern-day Nigeria.22 When this interdenominational church became associated with the Niger Delta Pastorate, Nicol and the Wesleyans broke away – but he was soon replaced from Lagos.23 He remained in the area for around a decade before returning to Sierra Leone to teach under the colonial government. Nicol was senior master at the Prince of Wales School in 1930.24

By the turn of the twentieth century, Westminster College had trained almost 5000 teachers.25 Its contribution to the history of education in Britain cannot be underestimated. The identification of William G. Nicol as the first person from Africa to attend the college – and so, the first black student to attend a predecessor institution of Oxford Brookes University – is an important step in recovering black heritage from the archives.

To find out more about Black History Month 2023 celebrations at Oxford Brookes University, click here.

- OCMCH. Westminster College Archives, Ph/a/3, college photograph album, 1893-1912. Accessible online, here. ↩︎

- We’re grateful to members of the ‘Old Photos of Sierra Leone’ Facebook group for their enthusiasm and input into the research for this blog post. ↩︎

- OCMCH. Westminster College Archives, B/1/a/5, register of teachers, 1894-1922. ↩︎

- Fourah Bay’s association with Durham began in 1876, with over fifty students earning degrees in its first decade or so. See, Matthew Paul Andrews, ‘Durham University: Last of the Ancient Universities and First of the New (1831-1871)’, unpublished University of Durham PhD thesis (2016). With thanks to Jonathan Bush, University Archivist at Durham, for more information. ↩︎

- ‘Old Fourah Bay College’, UNESCO World Heritage Convention [accessed at https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5744/ on 16 October 2023]. ↩︎

- Charles Marke, Origin of Wesleyan Methodism in Sierra Leone and History of its Missions (1913), p. 130. ↩︎

- Minutes of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference. ↩︎

- Thanks to Dr John Lenton for advice on this subject. ↩︎

- Marke, Origin of Wesleyan Methodism in Sierra Leone and History of its Missions, p. 165. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 168. ↩︎

- The Methodist Recorder (29 May 1905). ↩︎

- OCMCH. Westminster College Archives, B/1/a/5, register of teachers, 1894-1922. ↩︎

- The Westminsterian, vol. XIII, no. 6 (May 1904), p. 2. ↩︎

- The Westminsterian, vol. XIV, no. 3 (Christmas 1904), p. 16. ↩︎

- SOAS. MMS Box 794. File 1904. Item 22, letter from W. G. Nicol, to, W. H. Findlay, 26 April 1904; MMS Box 795. File 1905. Item 24, letter from W. G. Nicol, 15 July 1905; MMS Box 795. File 1905. Item 29, letter from W. G. Nicol, 9 August 1905. With thanks to Ed Hood at SOAS. ↩︎

- In 1901, the Rev. T. T. Campbell spoke in Burnley, and the Rev. C. W. L. Coker in Runcorn. See, Burnley Express (6 March 1901); Runcorn Examiner (3 May 1901). ↩︎

- The Westminsterian, vol. XIII, no. 7 (June 1904), p. 4. ↩︎

- Yorkshire Evening Press (26 August 1905). ↩︎

- The Methodist Recorder (29 May 1905). ↩︎

- Minutes of Wesleyan Methodist Conference (1911), p. 152. ↩︎

- Mercy Amba Oduyoye, The Wesleyan Presence in Nigeria, 1842-1962, An Exploration of Power, Control and Partnership in Mission (1992), pp. 107-110. ↩︎

- Rosalind I. J. Hacket, Religion in Calabar, The Religious Life of a Nigerian Town (1989), p. 79. ↩︎

- G. O. M. Tasie, Christian Missionary Enterprise in the Niger Delta, 1864-1918 (1978), p. 220. ↩︎

- Sierra Leone Blue Book (1930), p. 99. ↩︎

- OCMCH. Westminster College Archives, B/1/a/3, register of teachers, 1861-1896. Note on students figures by J. R. Langler dated 23 March 1898. Accessible online, here. ↩︎