This blog post is the first instalment in a series of regular Archive Spotlights, exploring stories from the Centre’s rich historic collections of archives, artworks, and printed works – and we begin with a International Women’s Day feature.

Sarah Smetham (née Goble) was born in October 1828, and baptised at the Wesleyan chapel in Milton next Gravesend in Kent. Her mother was the first of the family to join the Methodist society in that town, and her earliest quarterly ticket – preserved by Sarah throughout her life – dated to June 1815, the same day as the Battle of Waterloo. The Methodists in Gravesend were much ‘despised’ at that time, and this caused a breach in the family. Sarah’s mother gave up the fancy clothing of her youth and adopted the ‘plain cottage bonnet’ of the class. It was through the society that she met her future husband (Sarah’s father), though her family did not immediately approve of the union.

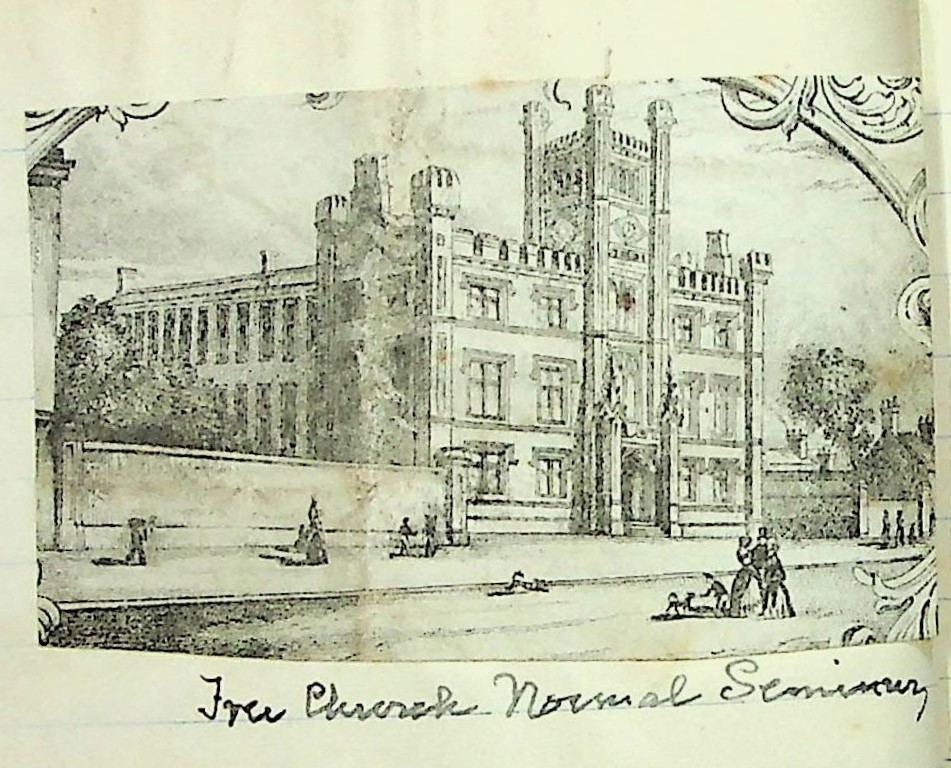

In Sarah Smetham’s early childhood, the family relocated to the village of Green Street Green some five miles away, where her father established a Sunday School class in their kitchen. They were also friendly with the local Anglican minister, who allowed Sarah to teach a babies’ class from the tender age of eight; ‘so I began the work of my life at a very immature age’. The family returned to Gravesend on her father’s death in 1839, and there she took all opportunities to educate herself by reading philosophy and science. At eighteen, Sarah was considered a strong candidate for further teacher training, and so following preliminary examinations, and with the consent of her mother, she embarked on the long journey to Glasgow to attend the Free Church Training College in preparation for a teaching career. At that time, this was the only option available for Methodist educators.

[c. 1840s]- [20th cent.]

Sarah soon came to the attention of the Rev. John Scott, who remarked that she gave ‘the best Bible lesson he had ever heard.’ With plans in motion to create a Methodist teaching training college in London, Sarah was appointed to the infants school in Westminster, which in 1851 was attached as a practising school to the newly-established Westminster Training College. She later reflected on her role in the early successes of the College, with Scott at the helm as it’s first principal,

London was crowded with visitors from all parts of the world and many of them found their way to the new College of Methodism … scarcely a day passed in which, without any warning, Mr. Scott would come in with a party, and desirous of showing off his pet schools to advantage would say in his suave way “Now Miss Goble will you kindly put the children in the Gallery and give them a lesson.”

The move to Westminster also quickly brought about the other most significant connection in her life. In that same year, the thirty-year-old artist James Smetham was appointed drawing master to the College. Almost fifty years’ after the event, Sarah recalled their first encounter in reminiscences for her children,

The first time I saw your father was on July 4th 1851. It was about half past four in the afternoon, the children had gone home and I was standing talking with Mr Langler by one of the windows which commanded the school entrance when he entered and crossed the playground to the College (then near its completion)… I little thought I should one day know him so well.

[c. 1840s]- [20th cent.]

The couple married in 1854, and over the next decade the family grew to include six children. At this time, James Smetham was moving on the periphery of Pre-Raphaelite circles and could count Ford Madox Brown, Gabriel Dante Rossetti, and John Ruskin among his friends. But, James’s art was never consistently financially viable and he struggled with profound mental health issues that affected his ability to work. Sarah remained her husband’s constant supporter and solace during these periods, and it frequently fell to her to provide for the family with her teacher’s salary.

This pattern persisted until the late 1870s, when James Smetham’s mental health collapsed for the final time. He became unable to work, or create artworks, and barely spoke for the final decade of his life. For many years before his death in 1889, he resided away from the family in lodgings where he could receive round the clock care.

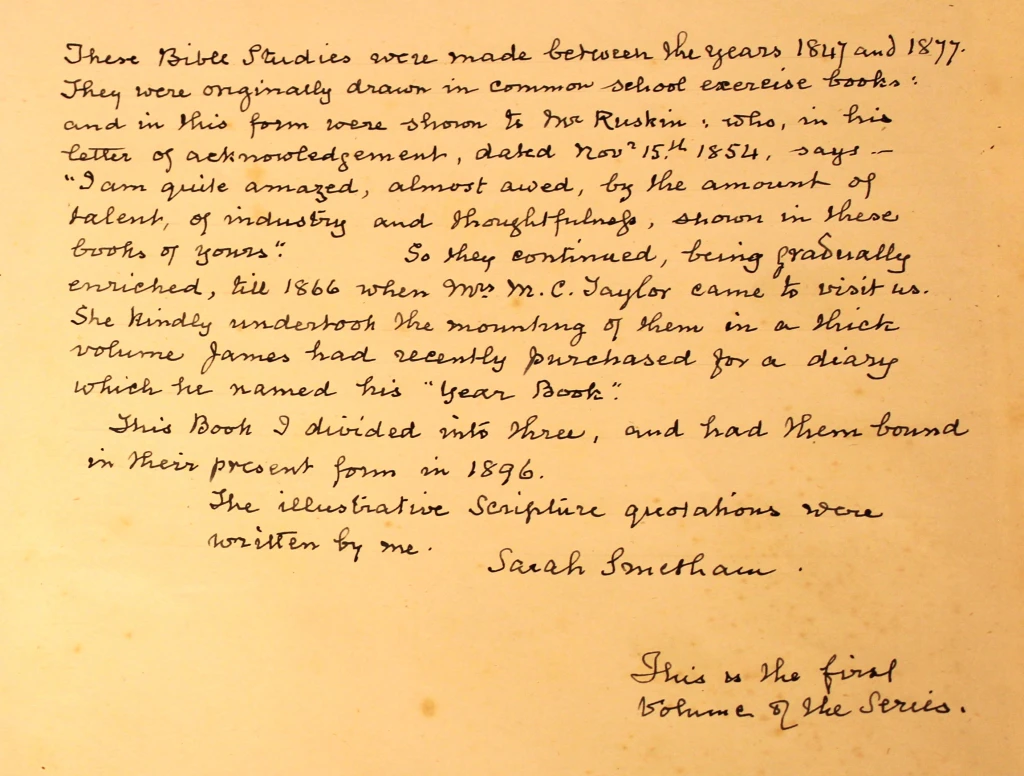

Following her husband’s death, Sarah Smetham became a champion for his artistic and creative legacy. She oversaw the publication of James’s letters and literary endeavours, and curated and embellished his partially-realised projects – including a series of Bible Studies that was greatly admired by Ruskin.

This continued into the final years of her life, as a new generation became interested in James Smetham’s artworks. When a series of previously-unpublished letters by her late husband appeared in the Wesleyan-Methodist Magazine in 1903, Sarah reached out to their editor directly,

I presume it is by some relationship to Mr Winders of Selby that the letters have come in to your possession… I am grateful to you for making them public. Had I had them when the volume was in preparation I should have included them

Sarah also permitted the loan of a treasured possession, her husband’s pocket New Testament which he had illustrated with his characteristic ‘squarings’, hoping it would meet with those ‘who have some memory of my dear husband.’ She also added,

I have always regretted that in the volume of the Letters more expression was not given to the Art side of his life. I wanted it at the time but the difficulties were great.

Sarah Smetham died in 1912. She belonged to a generation at the very forefront of Methodist teacher training expansion in the mid-nineteenth century, and – more particularly – was among the very first women to qualify under the new government examinations at that time. Her story is entwined with the first days, and earliest successes of, Westminster Traning College. It was there, of course, that Sarah also met her husband James. And we are indebted to her for the preservation and continued survival of many of his artworks and manuscripts that now form the Smetham Collection at the Centre.

To learn more about the Centre’s Smetham Bicentenary Project, click here