On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. The First World War raged for over 2,000 days before coming to a halt on 11 November 1918, and killed 880,000 members of the British forces, including 102 alumni of Westminster College. This amounted to 6% of the adult male population of Britain at the time, and it took much of the following decade for the College to recover.[1] Greatly reduced, Westminster was evacuated from London to Richmond College, the Wesleyan theological institution. In the second of our collection highlights, we explore what happened at the Westminster College site during the First World War, and its connections with the Australian armed forces.

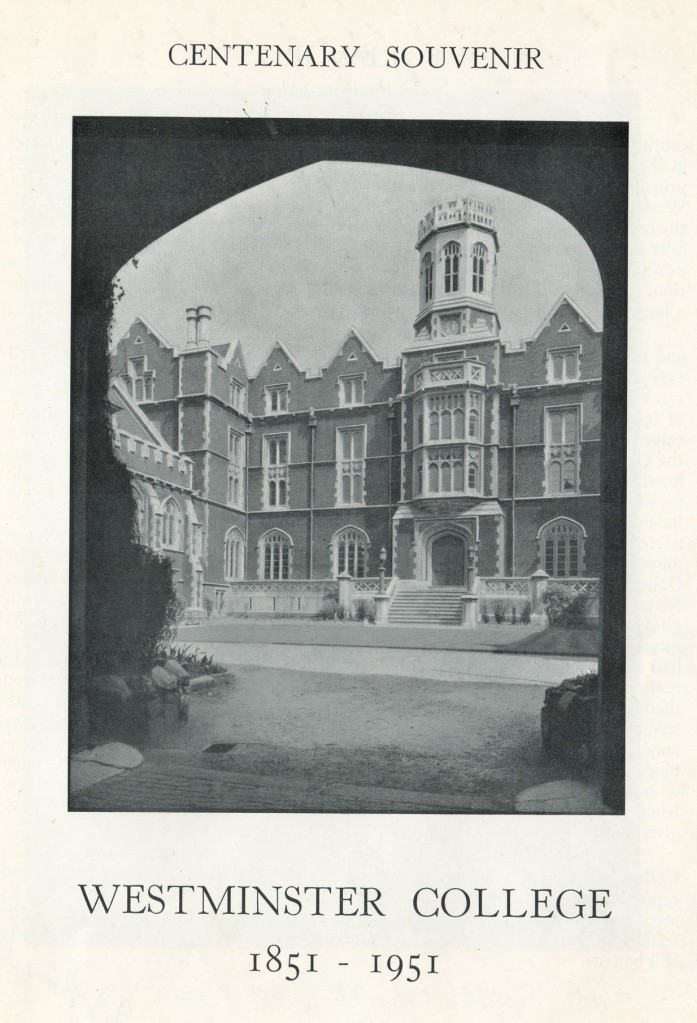

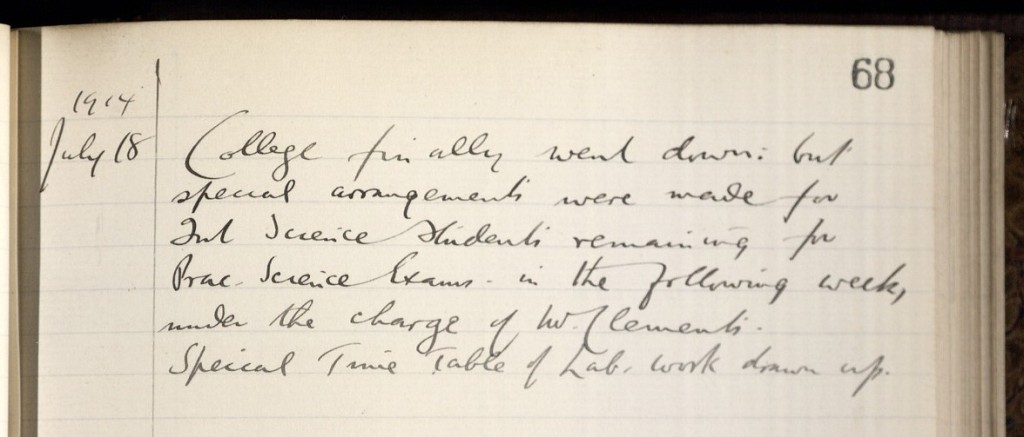

In July 1914, H. B. Workman closed his Principal’s log for the year by recording that ‘College finally went down’, suggesting that he was pleased to have reached the end of a long term![2] What he did not realise, however, was that he would be summoning groups of College men back to Horseferry Road in a matter of weeks so that students would be together if they chose to enlist.[3] The College continued to operate from London for twelve months, albeit it with a reduced cohort. The following year saw the College re-open in September 1915, only to be relocated to Richmond at the start of term. Workman later recalled,

I had finished my inaugural address to the new students on the morning of Thursday, 23rd September, and was about to go on with the usual routine of the day — the signing of indentures and so forth — when there came an urgent call for me at the telephone. It was from H.M. Office of Works to state that the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia were anxious to take our College as their military headquarters, and that officials would be round within the hour to survey the premises. They came, and before lunch the matter was practically settled: all that was left being the discussion of certain terms and conditions. They asked me to summon at once our various Committees. These duly met on the 30th September and unanimously approved the proposal. The Executive Committee of the Richmond Branch of the Theological Institution also unanimously and, with great graciousness, approved a proposal to hand over Richmond College to us and to transfer their students to Didsbury, Manchester. Within a week of the proposal first being mooted, the Australian Government were already beginning to lay down telephone wires and in other ways to effect the great change.

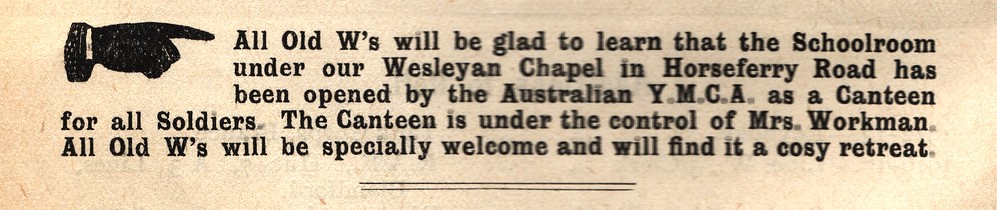

The College would remain at Richmond, and the Australians at Horseferry Road, until 1919. In his wartime memoirs James Green recorded that ‘Horseferry Road has its special place in our records’, before listing its achievements in both peace and war.[4] As the administrative headquarters for the Australian Imperial Forces, the College buildings were always extremely busy, with thousands of servicemen visiting the College buildings each week. Outside of the main College buildings, a sign labelling them as the ‘Australian Military Offices’ was erected, opposite a YMCA hostel ran by Mrs Workman (also in College buildings).

A Union Flag was placed in the middle of the Principal’s Quad, and a cannon added in its corner. Inside the buildings, Captain H. C. Smart organised offices which financed the Australian war effort, and also kept track of convalescents being returned from France. Smart ‘organised a records office, employing a few military supervisors with a large number of girls, whose labour was as effective as that of the soldiers, and much cheaper’.[5] They were surrounded by the trappings of College life – ‘working in libraries surrounded by memorial busts and bronzes of old Masters, Tutors, and Scholars. They see hundreds of clerks working in lecture-halls, class-rooms, or College Chapel’.

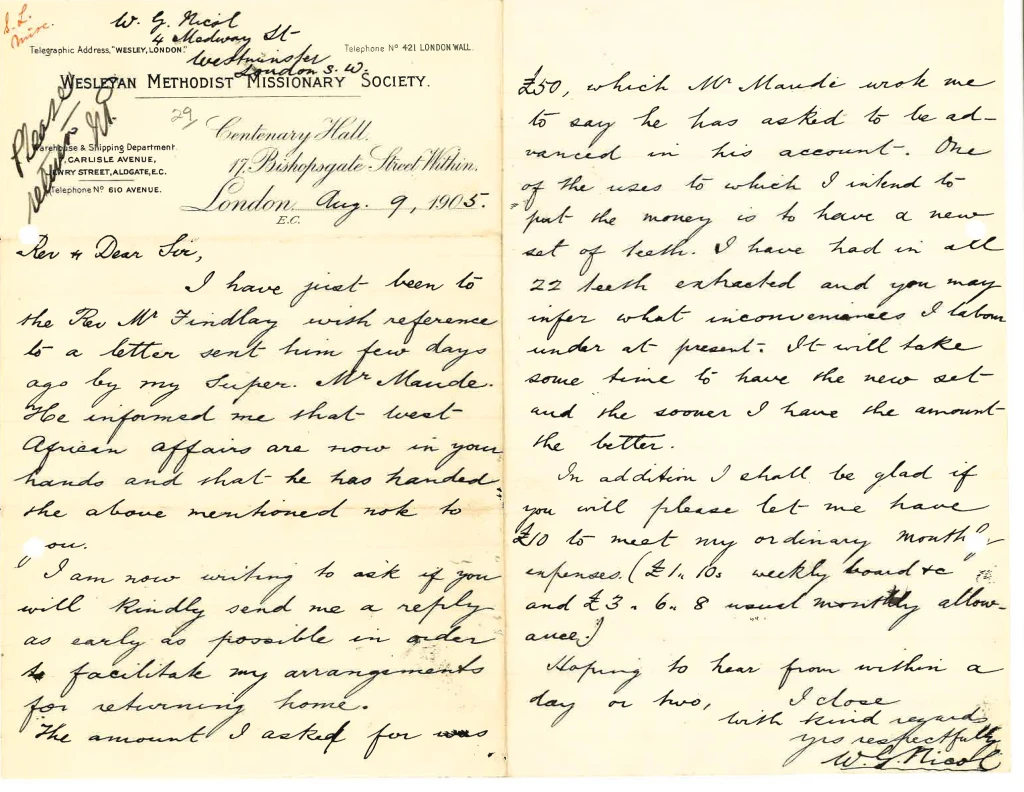

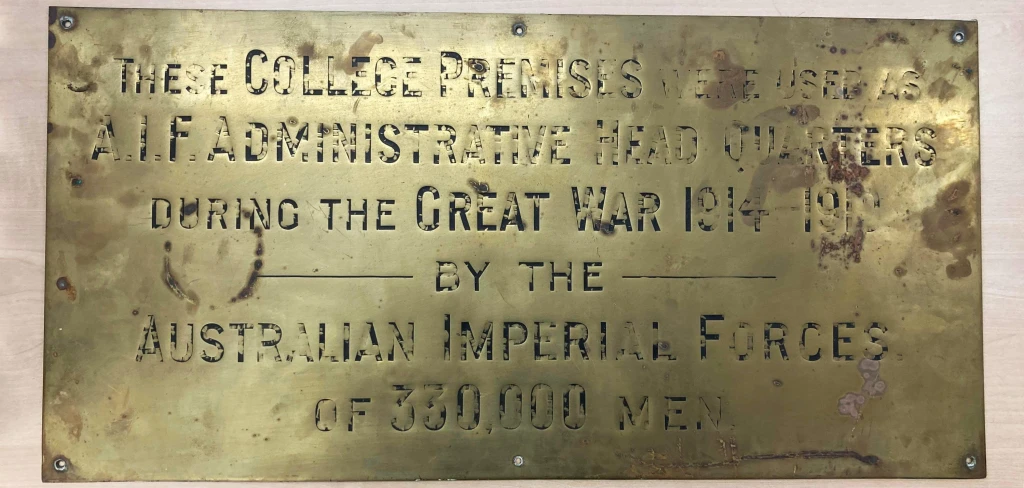

This flurry of activity did not go unnoticed: George V and Queen Mary visited in October 1917, inspecting a contingent of recovering Australian men.[6] Following the cessation of war in 1918, Westminster College memorialised its former students through a series of panels in its Chapel; the alumni society did the same for its members through the installation of an organ; and the Australians contributed a brass plaque to be set up in the buildings. Today, there is another plaque recording the College’s use by Australian forces, and it was believed that this plaque was long since lost – either during the Second World War, or left behind when Westminster moved to Oxford in the 1950s. But it has recently been rediscovered at the Harcourt Hill campus, hidden for the past twenty-five years.

These College Premises were used as

A.I.F. Administrative Head Quarters

during the Great War 1914-1918

by the

Australian Imperial Forces,

of 330,000 Men.

More poetically, James Green closed the Horseferry Road section of his memoir by noting that, ‘to Horseferry Road the Australian came gladly, leaving it regretfully for war again; and when the war is over it will be a kindly memory. In close proximity to Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament, where so many bonds of Empire are forged, the old Westminster Training College will continue to do its useful part in Empire building’.

ANZAC Day on 25 April is the national day of commemoration of Australia and New Zealand for victims of war and for recognition of the role of their armed forces. You can view more wartime records from the Centre’s collections, here.

[1] https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/research/olympic-britain/crime-and-defence/the-fallen/

[2] Westminster College Archives. A/3/c/2, Principal’s log book, 1911-14.

[3] Pritchard, The Story of Westminster College (1951), p. 110.

[4] https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/67351/pg67351-images.html

[5]https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2130826#:~:text=The%20Horseferry%20Road%20offices%20(formerly,High%20Commissioner%20in%20October%201915.

[6]https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C364528?image%3D2&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1713886293620759&usg=AOvVaw0QxFkYnJSg98qIPYRWUPMj